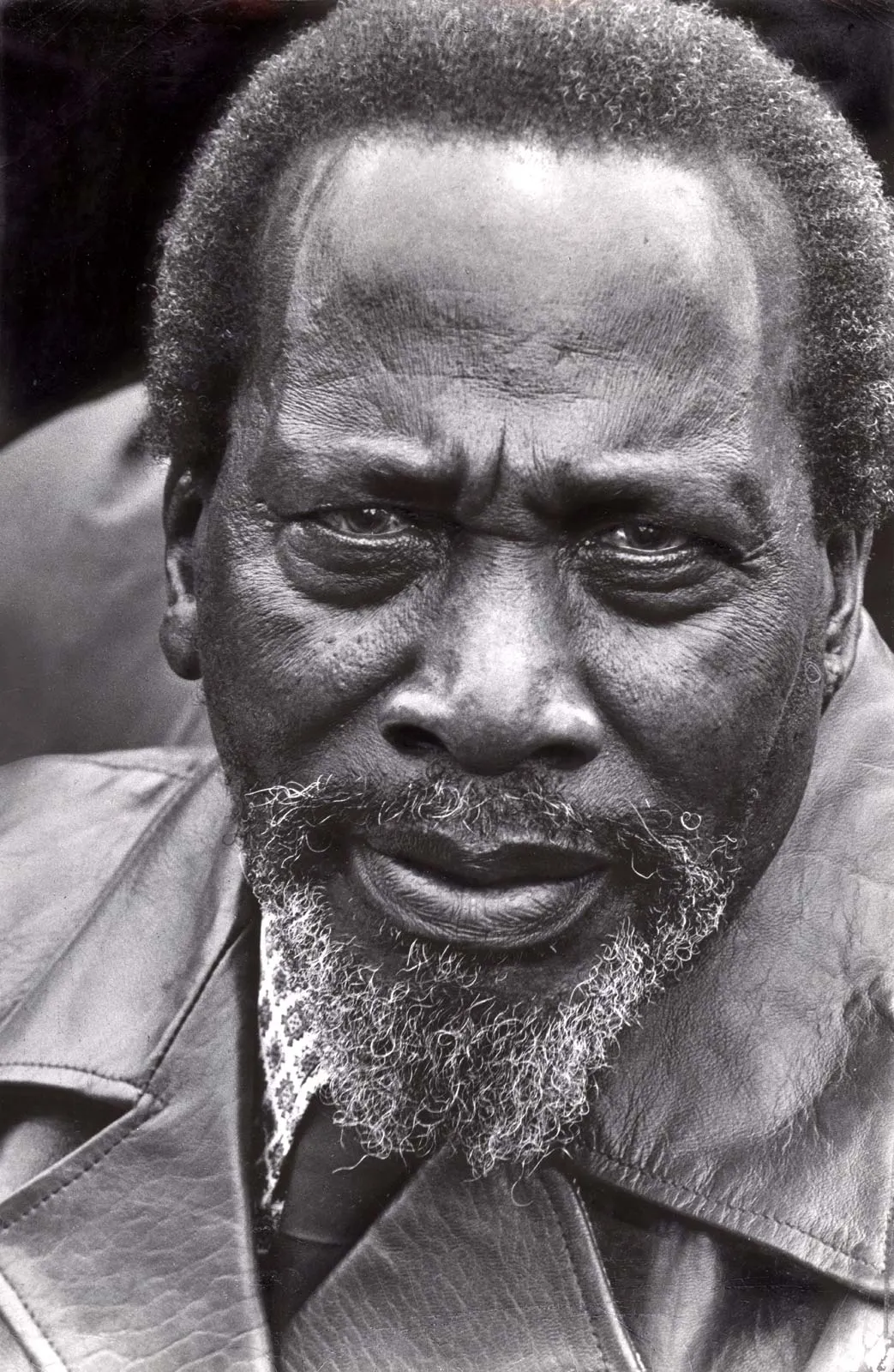

On August 21, 1961, Jomo Kenyatta, a pivotal figure in Kenya’s struggle for independence, was released from nearly nine years of imprisonment and detention by British colonial authorities.

Kenyatta’s release came as a significant step towards Kenya’s eventual independence, which was achieved two years later, leading to his appointment as prime minister.

Once viewed as a formidable emblem of African nationalism, Kenyatta’s leadership ultimately brought stability to Kenya and safeguarded Western interests during his 15-year tenure.

Kenyatta, born in the East African highlands near Mount Kenya in the late 1890s, belonged to the Kikuyu ethnic group, Kenya’s largest. Educated by Presbyterian missionaries, he moved to Nairobi, the colonial capital, in 1921.

There, he became active in nationalist movements and, by 1928, served as the general secretary of the Kikuyu Central Association, advocating against the appropriation of tribal lands by European settlers. Despite his early protests in London, which were met with indifference, Kenyatta persisted in his efforts to advance African rights.

In the 1930s, Kenyatta pursued formal education in Europe, including at Moscow University, and published “Facing Mount Kenya” in 1938, a notable work that highlighted the struggles of Kikuyu society under colonial rule. During World War II, he resided in England, engaging in lectures and writing.

Upon returning to Kenya in 1946, Kenyatta became president of the Kenya African Union (KAU) in 1947, advocating for majority rule. However, the white settler minority resisted substantial black participation in governance. The 1952 Mau Mau insurgency, a violent rebellion by some Kikuyu extremists, led to widespread unrest and Kenyatta’s trial and conviction for allegedly managing the Mau Mau organization. Despite his pleas of innocence and his commitment to nonviolence, Kenyatta was sentenced to seven years in prison.

Kenyatta spent six years in prison before being placed under house arrest in Lodwar. During this period, the British began transitioning Kenya towards self-rule. In 1960, the Kenya African National Union (KANU) was formed with Kenyatta as its leader. KANU’s stance was clear: no participation in government until Kenyatta was released. After promising to protect settler rights, Kenyatta was allowed to return to Kikuyuland on August 14, 1961, and was formally released a week later.

In 1962, Kenyatta traveled to London to negotiate Kenya’s independence. By May 1963, he led KANU to a pre-independence electoral victory. On December 12, 1963, Kenya gained independence, and Kenyatta was named prime minister. A year later, Kenya became a republic with Kenyatta as president.

Kenyatta’s leadership, which lasted until his death in 1978, was marked by efforts to foster racial cooperation, promote capitalism, and maintain a pro-Western stance. He established a one-party state and used his authority to curb political opposition.

His policies attracted foreign investment and contributed to Kenya’s stability. After his passing on August 22, 1978, he was succeeded by Daniel arap Moi, who continued many of his policies. Kenyatta, affectionately known as “mzee” or “old man” in Swahili, is remembered as the founding father of Kenya and a significant figure in African history.